“God’s not dead. He’s bread”

Five days ago I didn’t know who Sister Mary Corita was. But later that very day I opened the door to my mailbox and inside was the bright cover of the August edition of Sojourners magazine with the words, “A Joyous Revolution” across the center. I sat down to flip through the issue and started reading the featured article.

Sister Mary Corita was known as the pop art nun. In 1962 Sister Mary encountered Andy Warhol’s famous Campbell soup cans and was moved by the idea of seeing art in the ordinary. One of her students said this about her, “She was looking at it from, how do we bring this into our spirituality and God’s creation, seeing the gifts we have been given with food and the ordinary?”

I think many of us can close our eyes and picture the infamous Campbell Soup Can label. In the kitchen of my childhood home hangs a piece of folk art. Tiny compartments are filled with pantry staples, their familiar logos sealed behind a piece of glass, their original vibrant colors fading. It was a shrine, of sorts, to the common food.

These ordinary, common labels were elevated to high art. Warhol’s Campbell soup has fetched 11.8 million dollars at auction. Those pantry staples are symbols. They are symbols, for some, of survival.

I don’t recall ever being hungry as a child, but it was in Kindergarten that I realized I was poor. Sitting across from one of my peers, we unzipped our lunch bags and started unpacking their contents. The little boy across me watched as I took my first few bites of sandwich. “Hey” he interrupted, “why is it that your sandwich doesn’t have any lunch meat on it?”

“What do you mean?” I responded. “Your sandwich, it just has white cheese and mustard on it.” I looked at my sandwich, and then his, “What is lunch meat?”

That day, when I got off the school bus I went inside and asked my mom, “Why don’t we have meat on our sandwiches?” She turned and looked at me and said, “because, Mark, we can’t afford lunch meat. It is expensive.”

I’ve never forgotten that moment, even though it happened to me 30 years ago. At the age of five, I became aware that I was missing out on things because my parents didn’t have as much money as other people. For the rest of my childhood and adolescence, I carried with me the anxiety of financial fragility.

Packets of ramen noodles, hamburger helper, canned green beans and cream corn, and campbell’s chicken noodle soup, their sodium-filled contents is what filled my stomach.

Many of Sister Mary’s art pieces focused on food and uplifting the ordinary. In a 1964 serigraph Sister Mary wrote this “Mary does laugh, and she sings and runs and wears bright orange. Today she’d probably do her shopping at the Market Basket.”

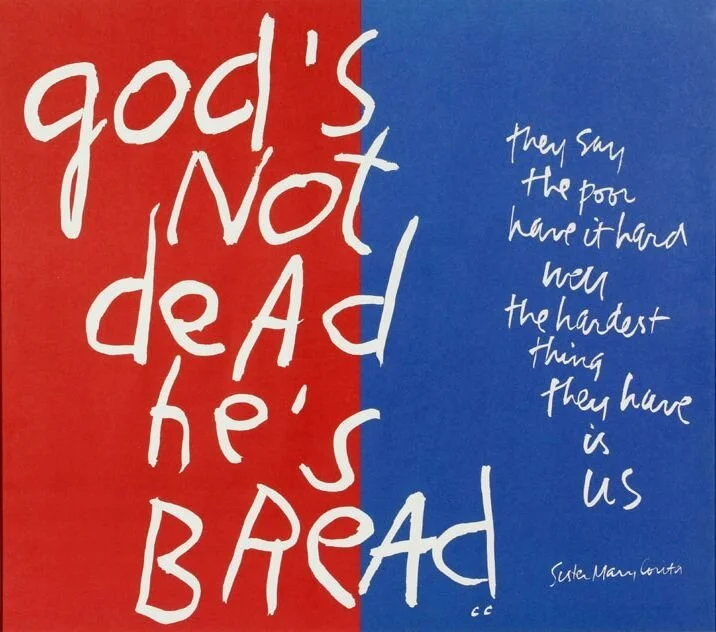

But another one of her pieces, commissioned for the 1968 Poor People’s March on Washington, hit me in the gut. It is a square piece. Split in two with a solid red rectangle on the left and a solid blue rectangle on the right. Over the background in white script it says, “god’s not dead he’s bread.” Next to it in smaller text it says, “they say the poor have it hard. well the hardest thing they have is us.”

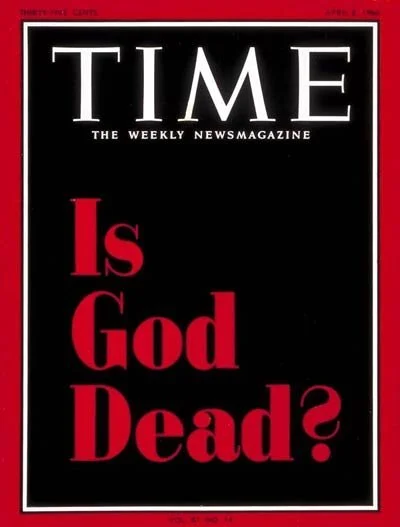

Two years prior to this commission, Time Magazine, in April of 1966 published its famous cover with black background and bold red lettering asking the question, “Is God Dead?”

Surely Sister Mary had this in mind as she put together this piece. Not to mention Nietzche’s famous proclamation in 1883 “God is Dead.”

A few weeks ago I gave a message about how strange it must be for people outside our tradition to see Christians saying they are drinking the blood and eating the flesh of Jesus. The wine and the bread. And our open worship time was filled with folks wrestling with their past experience with the eucharist.

In the Gospel of John Jesus says, “I am the bread of life. Whoever comes to me will never go hungry, and whoever believes in me will never be thirsty.”

It makes sense to me all the hangups we have about the strangeness of the eucharist. What is more frustrating is that the eucharist has been used as a tool of exclusion. Denying people the bread and wine as a way to say “You are, or are not in our family” seems to be the exact opposite of the message Jesus was giving us.

“God’s not dead, he’s bread” is a proclamation of the elemental, most simple presence of God in the world. I am all for proclaiming the death of the domineering god. That image of God needed to die. God as bread, God as love, God as the quiet breeze, those are subtle, and yet ever-present and life-giving presences. God being everywhere isn’t about suffocation. God being everywhere is about all that which gives us and our neighbors life. As simple as a piece of bread, or a can of chicken noodle soup.

And yet, as Sister Mary includes in this piece, the hardest thing the poor have is us. We have stigmatized hunger and poverty. Jesus saying that whoever comes to me will never go hungry or thirsty is a reminder that if nothing else, we followers of Jesus embody Christ by the most simple and fundamental presences in the world, feeding those who are hungry, with no conditions, with no judgment.

During World War II orphanages, sadly, were overflowing with children who lost both parents during the war. Most of the orphanages during that time were ran by the Catholic church. The Nuns began noticing the number of children struggling to sleep at night.

As they spoke with some of the orphans a theme emerged about their restless nights. The children were going to sleep worried they would not have food to eat the next day. An essential need, fulfilled by their parents, was now uncertain. Who was going to feed them? The nuns had an idea. They asked the kitchen to begin baking tiny loaves of bread each day. At night as they tucked the children into their beds, they put the loaves of bread in their arms. When they woke up in the morning they knew they would have their daily bread. The children began sleeping through the night again.

Five years before her death Sister Mary created a piece with these words, “You—special, miraculous, unrepeatable, fragile, fearful, tender, lost, sparkling ruby emerald jewel, rainbow splendor person—It’s up to you.”

It is us. Ordinary people. Fragile, tender, sparkling, rainbow splendor people who carry that of God in our hearts, our bodies. We don’t need to work so hard, to study theology for years, to close our eyes and focus really, really hard to hear God’s voice. It is here, visible with our two eyes. We taste it on our lips. We sip it up with a spoon. We water it with a hose in the morning, we dip our feet into it.

“god’s not dead. god is bread.”

Some queries :

Think about last week. If you can, try to remember a moment that you felt nourished. Was it a drink of cold water? Or that moment when you noticed a honeybee touching down on lavender? What was the moment? What if you allowed yourself to trust that this was a sacred moment? What happens for you if you let yourself do that?

If we framed our work and mission as a faith community around a simple, elemental presence for our neighbors, what would that look like? What has it looked like for you in your life?