The Quaker Legacy of Indian Boarding Schools

“If we have any hope to more closely approach unity with the Divine, we must seek to be transformed by that measure of the Light that is only available to us through someone else.”

Read Matthew 4: 1-11 (First Nations Version)

Some of you may be familiar with C.S. Lewis’s book The Screwtape Letters. For the unfamiliar, the book is written in an epistolary style, a fictional collection of thirty-one letters written between a senior demon named Screwtape, and his nephew, a junior tempter named Wormwood who seeks advice on how to secure the damnation of a British man who is referred to only as “the patient.”

C.S. Lewis

Screwtape offers guidance on the clever, and not-so-obvious ways to tempt someone away from compassion and love, towards isolation and despair, saying things like, “tortured fear and stupid confidence are both desirable states of mind.”

I first read this book in college, as I was trying to sort out my life as a Christian apart from the pressure to evangelize and save people from Hell. There were moments when I felt uncomfortable reading The Screwtape Letters sensing that in the hands of an evangelist, this book can feel like a training manual on how to convince someone that their lives have been taken over by Satan.

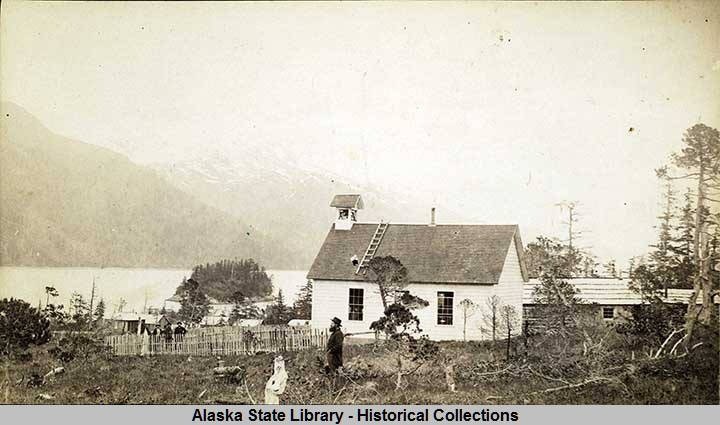

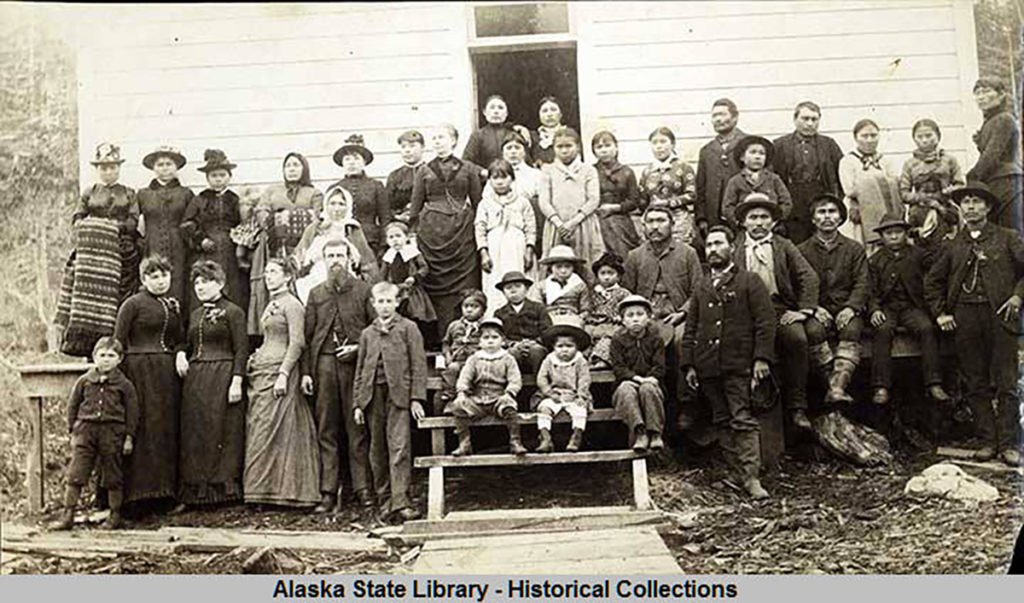

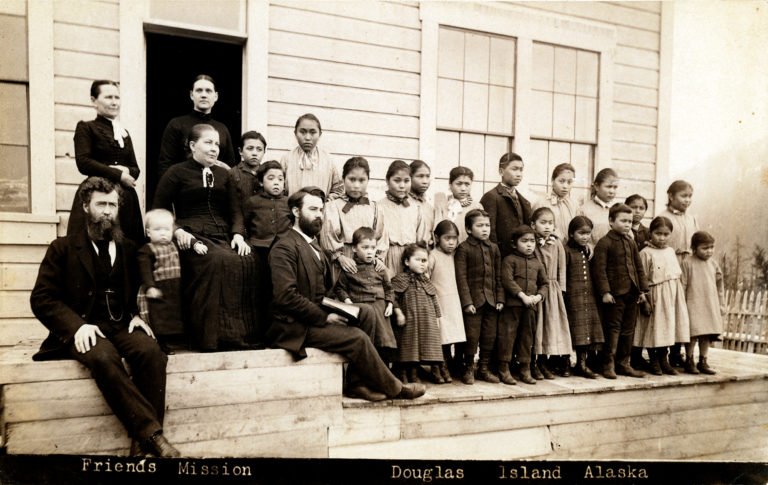

But I thought about The Screwtape Letters this week as I set my intentions to this morning and offering a message to all of you following last weekend’s gathering of Sierra Cascades Yearly Meeting of Friends. I felt clear that I needed to share the incredible gift given to us in the form of the vulnerable sharing of Native Alaskans who survived the horrors of Indian boarding schools. Thirty of which Quakers built, sustained and operated from the late 1800s until the early 1900s.

Their stories were a gift to us because people who’ve been traumatized by us do not owe us their stories of suffering.

As we listened to the ways in which Quakers systematically and forcefully removed children from their families, and stripped them of their names, clothing, language, and culture, I could see and hear the ways in which those painful memories still hurt. I was in the room for the heavy silence as they confronted, again, the images and feelings of those painful memories. These people were risking re-traumatization for my education, staring into a room of white faces, some of which have ancestral connections to the colonizers who worked in the schools where these horrors were unfolding.

As I listened I felt, at moments, red-hot anger for the Quakers, who, likely at yearly meeting gatherings much like we just had, sat in silence, with their heads bowed, and listened to their inward teacher as the community collectively discerned to spend tremendous amounts of financial resources to build and support these schools.

I thought about how in yearly meetings Quakers put out the call for missionaries to staff these schools.

I felt anger that we discerned it to be God’s leading to establish these schools to strip the most human parts of children: their names, their relationship with their parents, and tribe.

The words they learned from the mouths of mothers and their elders were treated like cuss words, labeled filthy, and often cleansed with lye soap on their tongues. How, how, how, did we Friends believe this was what God wanted us to do?

I sat with this uncomfortable reality, knowing that even though Friends are heralded for our progressiveness on social justice concerns, we participated in and benefited from slavery, and of the genocide of Native peoples for decades before prophets in our midst like John Woolman, Lucretia Mott, and Benjamin Lay were finally able to break through the spell we were under.

John Woolman

Born in New Jersey in 1720, Woolman became a well known Quaker abolitionist and activist for Native rights.

Woolman cautioned Friends of following “the wrong spirit,” speaking of the spread of Quaker’s involvement in the oppression of Native peoples and the isolation he experienced while speaking against it said, “And in this lonely journey I did this day greatly bewail the spreading of a wrong spirit…”

He later calls out Quakers naming the moral confusion that results from self-deception as “the secret workings of the mystery of iniquity (immoral behavior), which under a cover of religion exalts itself against that pure spirit with leads in the way of meekness and self-denial.”

The cunning nature of Screwtape speaks to the twisted ways in which evil squirms into our lives, presenting as love, or service, but which actually has, at it’s root, some kind of self-fulfillment that requires the exploitation of another person’s labor, resources, culture, or humanity. When this happens, when our good intentions become confused and mixed up with the hopes and desires of an oppressor, we find ourselves in business meetings where we seem to go out of our way to ignore Spirit, and instead follow the spirit of fear, or power, or prosperity, or legacy, or reputation, that all seem to be void of the "meekness and self-denial” that Woolman notes being signs of movement of “that pure spirit.”

That a person can profess to follow the life and teachings of Jesus Christ, alongside the vision for America as imagined by Donald Trump points to just how cunning systems of violence, hatred, and domination are. They can take root and eventually be accepted as orthodoxy, giving the majority the privilege of leveraging “certainty” or “just telling it like it is” against people who just can’t seem to accept the uncomfortable truth that they certainly have.

And yet we progressive Christians are not immune, because for decades we Friends rejected the prophets among us calling us away from this “wrong spirit” and back to the “pure spirit which leads in the way of meekness and self-denial.” I believe we, here at West Hills Friends, have been right to be weary of talk of sin, as it has been used as a tool to shame us and a weapon to deny LGBTQIA+ people of the God-given Truth of their sexual or gender identity.

And yet, I would hope that if our Alaskan Native friends were with us today they would be appreciative of our efforts to challenge the wrong spirit of colonialism that, like a parasite, has buried itself right next to the pure Spirit of God, so close that sometimes we have a hard time separating them out. The same is true of white supremacy, our in-grained belief in a gender binary, of homophobia, of our social status and reputation.

Ruby Sales

In the weeks following the murder of George Floyd, I had the honor of meeting Ruby Sales, one of the mothers of the civil rights movement on a small Zoom call with about six other faith leaders, all white and all pastoring progressive Christian churches. She said (paraphrasing) “I’m glad y’all are feeling a tiny bit of our anger, but I don’t want you to think that for a moment your hearts are all that far away from Derek Chauvin, who kneeled on George’s neck on that street. I need you, and your congregations to ask the question, “What is within your hearts that seems to require the need for black bodies to be harmed, or killed?”

The question startled me because I don’t think I have that requirement in my heart, but Ruby’s reminder is that, in a Screwtape sort of way, white supremacy has made itself at home in our hearts, and if we need any proof that it is there, just observe the defensiveness or the anger that bubbles up in us when we are confronted about this.

I’ve reached a point where I am concerned that you are looking up here at me, thinking sarcastically, “well, gee Mark, thanks for this shiny happy message on a nice July morning..” But, I think that if what we all take from this message, or the stories of our Native Friends is guilt and shame, our actions or response will be still rooted in that. They would not be sharing their stories with us if they did not have hopes for healing, of re-orienting ourselves, and if all we choose to do is wallow, then we will have done nothing but take again. Take these stories of suffering and just be sad about them. As I said on Sunday to those gathered for yearly meeting, we have done enough taking.

We’ve been challenged to look back and see the wrong spirit that was followed, and to make amends, and to seek out and address the other spirits which contend for our allegiance. It was a prompting for us to remember that when we move from that pure Spirit, we do tremendous, brave, imaginary, humble, disruptive, prophetic, and healing work in the world.

Reckoning with the ways in which we’ve messed up could lead us to be withdrawn, to being so painfully slow with our decision-making and activism that we end up missing the opportunity entirely. This is the balance I think we can find, and I think people like John Woolman still have things to say to us as we figure out this balance. I’ll leave you with this, which I hope helps us feel both humble and bold to move forward together as Friends.

““Some glances of real beauty may be seen in their faces who dwell in true meekness. There is a harmony in the sound of that voice to which divine love gives utterance, and some appearance of right order in their temper and conduct who’s passions are fully regulated….There is a principle which is pure, placed in the human mind, which in different places and ages hath had different names. It is however, pure and proceeds from God. It is deep and inward, confined to no forms of religion nor excluded from any, where the heart stands in perfect sincerity. In whomsoever this takes root and grows, of what nation soever, they become brethren in the best sense of the expression.” ”

Queries

Have you experienced the “harmony in the sound of that voice to which divine love gives utterance?” If so, what do you remember about the ministry offered? How did it feel?

As Friends, how are we striking a balance between prophetic and bold action, with the need to season our leadings so as to not perpetuate or support systems that serve us, but which harm others?

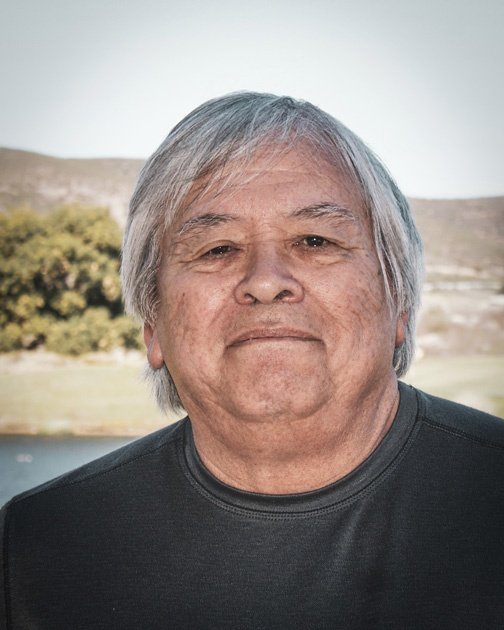

Jamiann S’eiltin Haselquist (Tlinqít)

Spoke to our gathering about practical things we can be doing. Below is a list with links to resources. Jamiann reminded us, “Earning Trust Won’t Come Without Action.”

-

For more information about the Alaska Native Claims Settlment Act following the link below. Jamiann shared that Quakers may be holding on to some of these claims to this day.

-

What if our Quaker communities committed to rooting out colonization in our Meetings?

-

How are we familiarizing ourselves with the workings of White Supremacy culture in our meetings?

A good place to start: White Supremacy Culture (What is It?)

-

Read more about how Quakers in Alaska did this by reading the linked Friends Journal article below

Alaskan Quakers apologize to Alaskan Natives for Indian boarding schools

-

We Quakers are known for our record keeping. Chances are many of us have documents with valuable pieces of information that Native families who were in Quaker-run boarding schools need.

Jamiann shared with us the work of the “Carlise Institute” which can serve as an example of this type of database work.

-

Do we Quakers have physical buildings that we can give to Native groups to use as healing/gathering spaces?

-

Has your Quaker community established relationships with the tribal lands in which we inhabit? If not, how might Spirit be moving you to bring this to your Meeting?